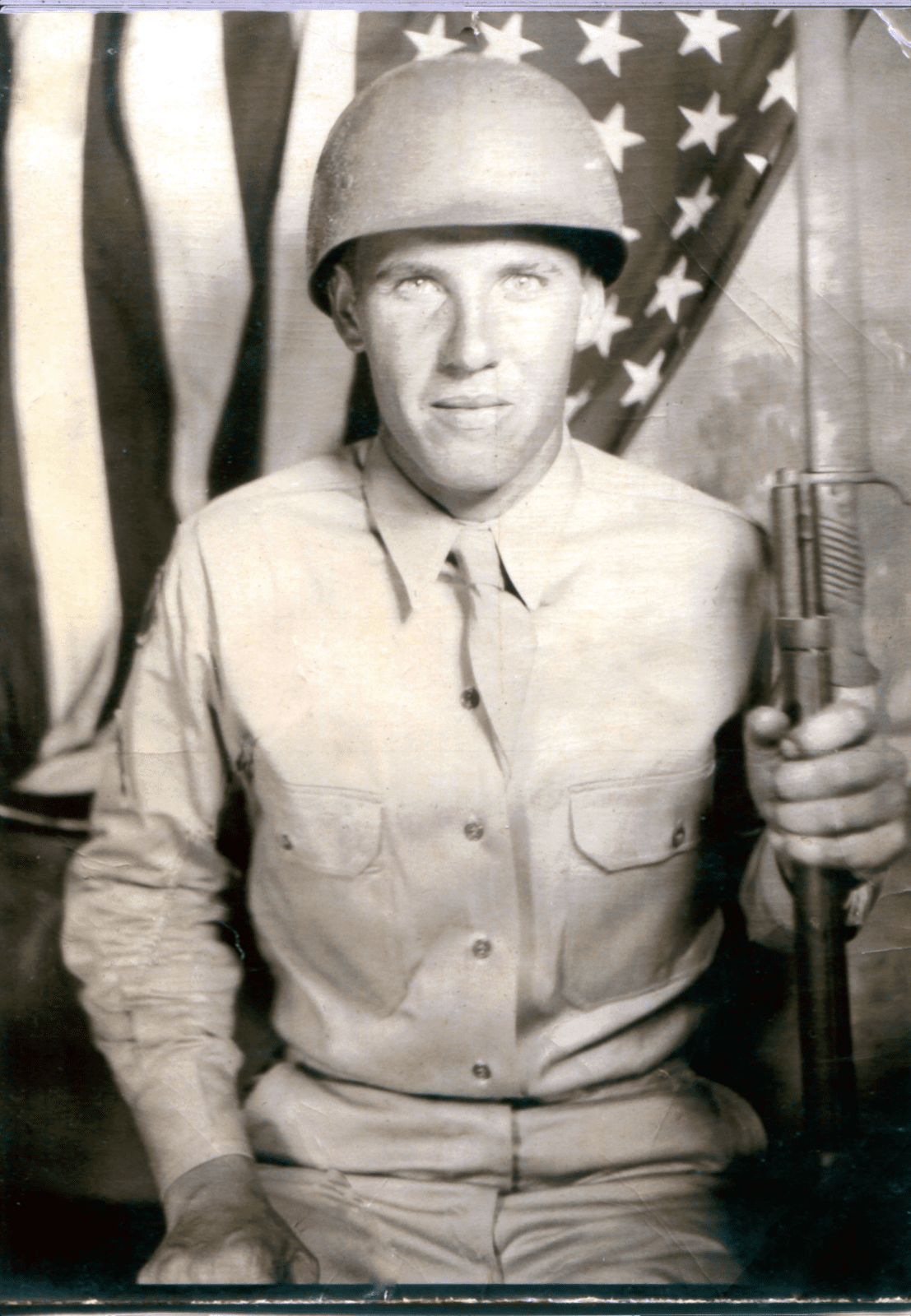

Clyde's Story

The advanced commando training Clyde's battalion went through lasted approximately three months. Immediately upon arriving at Fort William in northern Scotland, the recruits embarked on an exhausting forced march to their camp in the shadow of Achnacarry Castle, a trek that foreshadowed a month of rigorous training. The future Rangers endured log-lifting drills, obstacle courses, and speed marches over mountains and through frigid rivers under the watchful eye of British commando instructors. In addition, they received weapons training and instruction in hand-to-hand combat, street fighting, patrols, night operations, and the handling of small boats. The training stressed realism, including the use of live ammunition. On one occasion, a Ranger alertly picked up a grenade that a commando had thrown into a boatload of trainees and hurled it over the lake just before it exploded. In early August, the battalion transferred to Argyle, Scotland, for training in amphibious operations with the Royal Navy and later moved to Dundee, where they stayed in private homes while practicing attacks on pillboxes and coastal defenses.

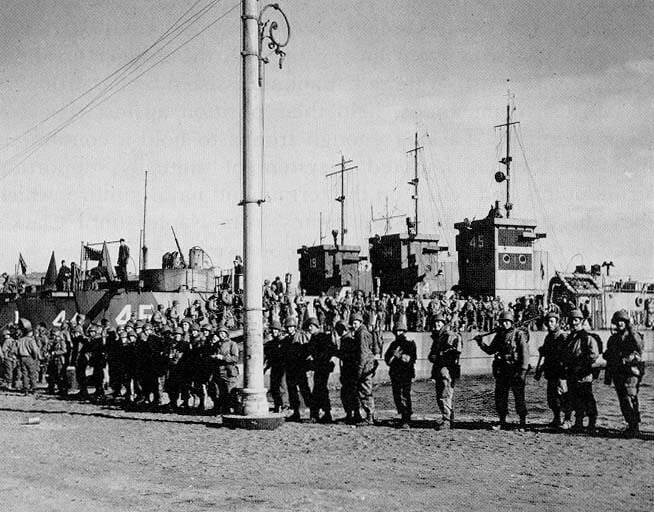

In late July, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff under pressure from a president anxious for action against the Germans on some front, reluctantly bowed to British arguments for an invasion of French North Africa, code named Operation TORCH. As planners examined the task of securing the initial beachheads, they perceived a need for highly trained forces that could approach the landing areas and seize key defensive positions in advance of the main force. Accordingly, Darby's battalion received a mission to occupy two forts at the entrance of Arzew harbor and clear the way for the landing of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division of the Center Task Force.

The performance of the Rangers in their first independent mission reflected their emphasis on leadership, training, and careful planning. In the early morning hours of 8 November, two companies under Darby's executive officer, Maj. Herman W. Dammer, slipped through a boom blocking the entrance to the inner harbor of Arzew and stealthily approached Fort de la Pointe. After climbing over a seawall and cutting through barbed wire, two groups of Rangers assaulted the position from opposite directions. Within fifteen minutes, they secured the fort and sixty startled French prisoners. Meanwhile, Darby and the remaining four companies landed near Cap Carbon and climbed a ravine to reach Batterie du Nord overlooking the harbor. With the support of Company D's four 81-mm. mortars, the force assaulted the position, capturing the battery and sixty more prisoners. Trying to signal his success to the waiting fleet, Darby, whose radio had been lost in the landing, shot off a series of green flares before finally establishing contact through the radio of a British forward observer party. The Rangers had achieved their first success, a triumph tempered only by the later impressment of two companies as line troops in the 1st Infantry Division's beachhead perimeter. Ranger losses were light, but the episode foreshadowed the future use of the Rangers as line infantry.

Ultimately Clyde ended up with his Battalion at a place called the Kasserine Pass fighting against General Field Marshall Rommel and his Panzer units. In the early hours of the 19 February 1943 Rommel ordered the Afrika Korps Assault Group from Feriana to attack the Kasserine Pass. The 21st Panzer Division at Sbeitla was ordered to attack northward through the pass east of Kasserine which led to Sbiba and Ksour. During the battle between German and US forces Clyde was wounded the first time. He was treated and released back to his unit after healing.

The US and combined Allied forces were eventually able to drive Rommel from North Africa and Clyde and his Ranger battalion were reassigned to Sicily. In Sicily, the Rangers served first as assault troops in the landing and then in various task forces in the drive across the island. At Gela in the early morning darkness of 10 July 1943 the 1st and 4th Ranger Battalions, under Darby and Maj. Roy Murray, attacked across a mined beach to capture the town and coastal batteries. They then withstood two days of counterattacks, battling tanks with thermite grenades and a single 37-mm. gun in the streets of Gela.

As Allied forces expanded the beachhead, one Ranger company captured the formidable fortress town of Butera in a daring night attack. To the west, Dammer's 3rd Ranger Battalion moved by foot and truck to capture the harbor of Porto Empedocle, taking over 700 prisoners. In the ensuing drive to Palermo, the 1st and 4th Ranger Battalions joined task forces guarding the flanks of the advance, and the 3rd Ranger Battalion later aided the advance along the northern Sicilian coast to Messina by infiltrating through the mountains to outflank successive German delaying positions. The fall of Messina on 17 August, 1943 marked the end of the Sicilian campaign and the Rangers were already preparing for the invasion of Italy.

At Salerno, the Rangers once again secured critical objectives during the amphibious assault, but cut off by the rapid German response to the main landings, were forced to hold their positions for about three weeks, a defensive mission unsuitable for such light units. Landing on a narrow, rocky beach to the left of the main beachhead early on the morning of 9 September, the Rangers quickly occupied the high ground of the Sorrentino peninsula, dominating the routes between the invasion beaches and Naples. To the south, the Germans contained the main landing, preventing Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark's Fifth Army from linking up with the Ranger position. Nevertheless, Darby's three battalions, assisted by paratroopers and British commandos, held their position against repeated German attacks. Lacking enough troops to hold a continuous line, the Rangers adopted a system of mutually supporting strongpoints and relied on the terrain and naval gunfire, which they directed to harass the routes from Naples until Clark's force broke through to them on 30 September, 1943.

Casualties mounted when the Rangers served as line infantry in the offensive against the German Winter Line. Lacking troops on the Venafro front, Clark used the Rangers to fill gaps in Fifth Army's line from early November to mid-December. Attached to divisions, the battalions engaged in bitter mountain fighting at close quarters. Although reinforced by a cannon company of four 75-mm. guns on half-tracks, they still lacked the firepower and manpower for protracted combat. By mid-December the continuous fighting and the cold, wet weather had taken a heavy toll. In one month of action, for example, the 1st Ranger Battalion lost 350 men, including nearly 200 casualties from exposure.

A botched infiltration mission on the Anzio beachhead in early 1944 completed the destruction of Darby's Rangers. The Allied invasion of Anzio was an attempt to break the stalemate in Italy. The advance was painfully slow and bloody. The Allies hoped with a “hook” around the German defenses at the Gustav line, that they could move on to Rome, bypass the main German defensive lines without risking a frontal assault and take the vital airfields around Rome. After a nearly unopposed Allied amphibious assault on 22 January 1944, Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas, commander of the VI Corps, failed to press his advantage, and the Germans were able to contain the Allies within a narrow perimeter. Seeking to push out of this confined area, Truscott, now a major general and commander of the 3rd Infantry Division, ordered the 1st and 3rd Ranger Battalions to infiltrate four miles behind enemy lines to the crossroads town of Cisterna. One hour after their departure, the 4th Ranger Battalion and the rest of the division would launch a frontal assault and use the confusion created by the infiltrating Rangers to drive a deep wedge into the German defenses. American intelligence, however, had failed to notice a large German buildup opposite the American lines, and Ranger reconnaissance of the target area was poor. The Americans believed that the main line of German resistance was behind Cisterna. That was wrong. In fact, the Germans used the town as an assembly area for its reserve troops and had several units already in the area. Worse still was the failure to get the word to the attacking troops of this very fact. A group of Polish conscripts defected to the Americans and they all relayed to the Americans about the buildup, but no one relayed the information to the Rangers in time.

The Rangers began their infiltration movement with two Battalions on 28-29 January, 1944 at 0130. All was seemingly going well, they bypassed several German positions, wading at time, in the waist-deep canal. They thought they had been undetected but the Germans had seen them and were laying in wait.

When daylight struck, the Rangers were still short of their objective. They were going to exit the ditch and cross the open terrain, but the Germans were ready. Perfectly placed machine guns put the Rangers under withering fire. Rather than attacking a thinly-held part of the line, the two lightly-armed Ranger Battalions were facing elements of the German 715th Infantry Division and the Hermann Göring Panzer Division. The Germans also had 17 MarkIV Panzers concealed in the town.

The murderous machine gun fire forced the Rangers back into the ditches, and the German tanks began to move forward, raking the ditches. Raking the ditches was a term used for describing when a German tank would drive on top of a fox hole or ditch and then would do a u-turn on top of the ditch so as to create as many casualties as possible in the ditch or fox hole. Major Dobson, the 1st Bn commander, personally knocked out one Panzer by shooting the tank commander with his pistol and then dropping a white phosphorous (WP) inside the hatch. Rangers captured two more, Mark IVs but other Rangers with bazookas not realizing this knocked them out. (This same story about Major Dobson was re-told to Jimmie Bayles, Clyde's oldest son, by Clyde. Clyde told Jimmie that he watched one of his commanding officers shoot the tank commander and drop a grenade inside the tank.)

The Rangers never stood a chance. The Germans put several Ranger POWs in front of their tanks and marched them to the ditch. The men had no choice, they either surrendered en masse or killed their own men. Of the 767 Rangers who began the operation, only six and one member of the Recon troop made it back to the American lines.

The main attack encountered heavy resistance and took heavy casualties. They were unable to reach their beleaguered comrades in time. Cisterna would remain in German hands until May. Clyde was wounded in this battle and left for dead. It was later discovered he was badly wounded, and he was operated on by a German Field doctor who saved his life. When Cisterna was recaptured so were the prisoners. Clyde had subsequently developed gangrene and was presumed dead or dying. When he was discovered to be alive, he was operated on and then flown to Britain for further surgery and hospitalization.

Once recovered, Clyde was offered a position to begin training new Ranger Battalions and Battalion leaders prior to the D-Day invasion. He refused the position, asking instead to be reassigned to his unit to fight alongside his brothers in arms. He did not want to be a "paper-pusher". He always ran "point" for his assignments because he wanted to be in front "so he could know what was going on" and "so the other men wouldn't have to put themselves in harm's way".

He was reassigned to the 4th Ranger battalion and ultimately ended up at the Battle of Monte Cassino, which would claim the lives of 55,000 US and Allied forces. During the battle, Clyde was once again near fatally wounded. As a result of the battle, he lost a lung and sustained shrapnel and bullet injuries to his arms and back. He was told at that time that it was likely he might never walk again. He was shipped home semi-paralyzed.

Once home, Clyde set about to make things happen and true to his nature, went on to prove his doctors wrong. After many long months of rehabilitation, he was eventually able to walk again.

Clyde re-enrolled in college, and ultimately graduated from Mississippi College with a degree in Chemistry. He was then accepted to Medical School at Memphis State where he started medical school, but quickly realized that he was unable to support his family with the job opportunities that were available and attend medical school full time. He ultimately withdrew and returned to Jackson, Mississippi, where he joined a Chemical company and became the Head Chemist so that he could support his family. In 1967, at the age of 45, Clyde was diagnosed with a Sinus Cancer that eventually spread to his brain. At the time of diagnosis, he was given 6 months to live. As usual, Clyde was unwilling to let others determine what he could or could not do. With persistence and unyielding determination, he went on to survive another 6 years. He died in January 1974 a few years after his daughter Patricia was born.

The Rangers did not have a motto until after D-Day. It was during the bitter fighting along the beaches and the heroism and in North Africa, Sicily, Italy and the Beaches of Normandy that the Rangers eventually gained their motto, "Rangers, lead the way!".

Clyde Bayles was a rare man who left a legacy that is still felt today. He received the Purple Heart, the Bronze Star, the Oak Leaf Cluster and numerous other awards. He was a hero, husband, friend, brother, father and a man who led the way in all that he did.

It is only fitting that his daughter, Patricia, would name her company in honor of her father who represented everything good in this world. Clyde I seeks to lead in business in the same spirit of James Clyde Bayles, with the integrity, courage, and unwavering determination to take the "point" on tough issues and assignments and to dedicate itself and its people to its partners and their projects.